Neuroscience

•

2025-08-20

Why the prefrontal cortex (frontal lobe) matters

By Dr. Emilė Radytė, CEO of Samphire Neuroscience

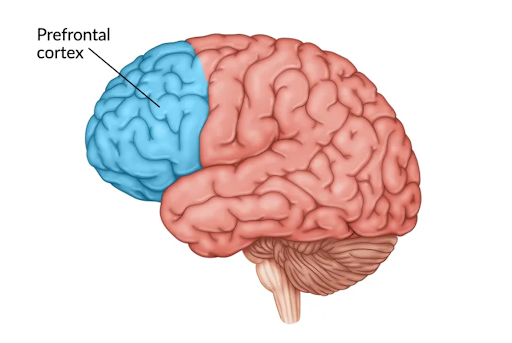

What is the Prefrontal Cortex?

When people talk about “executive function,” they’re really talking about the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This is the area of brain tissue right behind the forehead that is the control room for goal-directed (i.e. any meaningful) behavior. It integrates what you perceive, remember, and feel, then helps you choose what to do next. The PFC doesn’t work in isolation: it’s wired into large-scale networks that include sensory areas, memory systems, and emotion circuits, so even modest changes in how it functions can ripple across how you think and feel.

Image sourced from 'Prefrontal Cortex Damage: Understanding the Effects & Methods for Recovery' by FlintRehab.com.

Frontal Lobe in Your Daily Life

An easy way to picture the PFC is to watch it at work in everyday life:

- Working memory - remembering your shopping list on the way to the store

- Attentional control - ignoring a notification while finishing a task

- Inhibitory control - deciding not to send that risky late-night message to your ex

- Prospective control - planning a difficult week and actually sticking to it

These are distinct skills and capabilities, and you may be better at some than others, but ultimately the PFC helps you coordinate all of these capabilities so that your short-term impulses don’t derail longer-term goals (and sometimes, it fails to do so!).

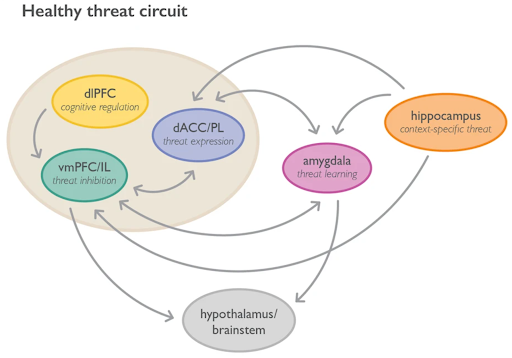

How the PFC regulates mood and emotion

Emotion regulation is where the PFC’s influence becomes most tangible. When regions deeper in the brain, such as the amygdala, flag a potential danger, they send a flag to the PFC. Then, the PFC can calm an escalating reaction by rethinking a situation (“this disagreement isn’t a catastrophe”) and switch off fear responses when a cue is no longer dangerous (“you’re on stage, the people watching your presentation will not actually eat you”). When these top-down signals from the PFC are strong and well-timed, you feel steady and in control.when they’re weak or mistimed, emotions feel louder and harder to shake,leading to “over-reactions”.

Example diagram of how areas of the PFC interact with other regions of the brain to evaluate whether a danger is real or not, reproduced from Kredlow et al., 2021 (Neuropsychopharmacology)

When the PFC doesn’t work properly…

Because the PFC is critical for regulating emotional response and decision making, it shows up in many psychiatric and neurological conditions. For example:

- In depression, a small region of the PFC, called the left dorsolateral PFC, is less active than in people without depression, which corresponds with low mood, indecision, and reduced cognitive control experiences.

- In anxiety disorders, another region of the PFC, the ventromedial PFC, seems to start connecting very tightly with the amygdala, making it harder to turn off the feeling of fear, even if there is no “active trigger” for it.

- In ADHD, the dorsolateral PFC seems to be under-active (and long-term those areas of the brain may even have reduced volume), which leads to variable attention and impulsivity, the inability to control decision-making and the priorities of different stimuli.

- In PMS/PMDD, there appears to be an imbalance in the communication between the left and the right PFC, which is only visible in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. As a result, the PFC becomes inefficient in managing emotion top-down (as seen with depression), leading to symptoms of low mood, indecision, and reduced cognitive control.

Targeting the PFC through brain stimulation

Non-invasive brain stimulation lets us engage with the PFC directly. With transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), a very low electrical current is applied across the scalp to shift the probability that neurons in targeted PFC regions will fire. This, essentially, trains the PFC to maintain optimal top-down control function, which allows you to stay in control of your feelings and decisions. And, importantly, this works very lightly at the brain level, always letting you stay in control and not suppressing otherwise healthy hormone production.

So, the PFC is not a “magic fix”. It is, however, the part of the brain that translates goals into actions, and emotions into choices. If you want steadier focus, better self-control, and calmer mood under stress, you want a PFC that’s well tuned and well connected to the rest of the brain.

That’s why, at Samphire Neuroscience, we start with helping you understand how your brain connects with your experiences first. From there, we help you take control to support how your brain manages everything downstream - from attention and planning to your every day (or every cycle) feelings.

References (selected)

Hettwer, M.D., Larivière, S., Park, B.Y. et al. Coordinated cortical thickness alterations across six neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Nat Commun 13, 6851 (2022).

Baehr, E., Rosenfeld, P., Miller, L., & Baehr, R. (2004). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and changes in frontal alpha asymmetry. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 52(2), 159–167.

Lin, I.-M., Tsai, Y.-C., Peper, E., & Yen, C.-F. (2013). Depressive mood and frontal alpha asymmetry during the luteal phase in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 39(6), 1023–1030.

Kenwood, M.M., Kalin, N.H. & Barbas, H. The prefrontal cortex, pathological anxiety, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 260–275 (2022).

Pizzagalli, D.A., Roberts, A.C. Prefrontal cortex and depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 225–246 (2022).

Zanto, T., Rubens, M., Thangavel, A. et al. Causal role of the prefrontal cortex in top-down modulation of visual processing and working memory. Nat Neurosci 14, 656–661 (2011). x

Ray, R. D., & Zald, D. H. (2012). Anatomical insights into the interaction of emotion and cognition in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(1), 479–501.