Neuroscience

•

2025-08-20

Do I have enough serotonin?

By Dr. Emilė Radytė, CEO of Samphire Neuroscience

Where does serotonin comes from?

Serotonin is produced both in the brain and the gut (!), but here’s the critical point: only the serotonin made in the brain affects mood, thinking, and emotional regulation. The brain’s serotonin comes from nerve cells in a structure called the raphe nuclei, deep in the brainstem. These neurons send serotonin widely: into the prefrontal cortex, (PFC; for planning, decision-making, and emotional control), the amygdala (for processing threat and emotion), and the hippocampus (for memory and stress regulation).

When serotonin levels or activity in these specific pathways drop, the effects can ripple across thinking, emotions, and behaviour. This is why serotonin is linked not just to depression, but also anxiety, irritability, and certain pain disorders.

Low serotonin: signs, symptoms, misconceptions

It’s tempting to think of serotonin levels like a fuel gauge, where high means happy, low means sad, but that’s not quite right.

Research shows it’s not only how much serotonin you have, but also how your brain’s serotonin receptors respond that matters. You might have “normal” serotonin levels, but if the receptors in the prefrontal cortex or amygdala aren’t responding efficiently, you could still experience mood or cognitive symptoms.

Possible signs that serotonin signalling isn’t optimal can include:

- Persistent low mood or irritability

- Increased anxiety or panic

- Changes in appetite or digestion

- Trouble sleeping

- Higher sensitivity to pain

None of these are diagnostic on their own, but together, especially if they track with your menstrual cycle or stressful life periods, they can be very important clues.

Hormones and serotonin: how your cycle affects your brain chemistry

For women, serotonin is closely intertwined with hormonal changes.

In the follicular phase, increasing estrogen boosts serotonin production and receptor activity, peaking at ovulation, when you might feel your best.

In the luteal phase, progesterone and its metabolites can indirectly influence serotonin pathways via GABAergic effects (read our article about how hormones work for PMS/PMDD to dive deeper). This is why some people experience mood shifts in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (the days before menstruation begins), even if serotonin levels aren’t “low” in the absolute sense. This is because the brain’s response to serotonin changes across the cycle.

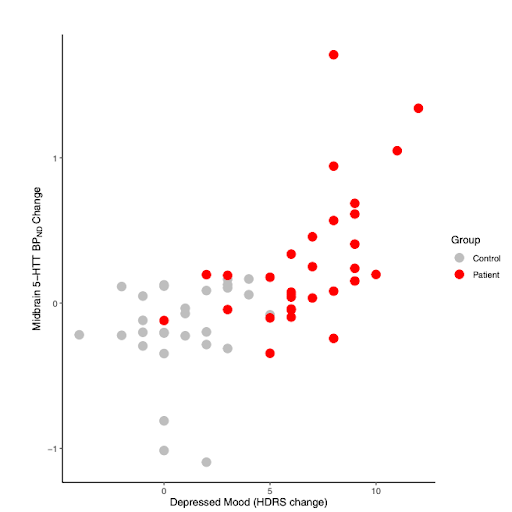

Graph showing how serotonin’s behaviour in the brain is linked to PMDD (patient) depression severity. In brief, when the brain is more sensitive to serotonin, it’s linked to higher depression in the luteal phase for people with PMDD, reproduced from Sacher et al., 2023 (Biological Psychiatry)

Can you measure serotonin levels?

Unlike cortisol, serotonin can’t be measured accurately with a quick blood test to assess brain levels. The best approach is to map symptoms, patterns, and triggers. Are mood changes random? Or do they line up with certain phases of your cycle or stress events? Tracking over time, especially alongside hormonal and lifestyle factors, gives a far clearer picture than a one-off measurement.

Samphire app - a brain-based cycle tracking app - help you log mood, sleep, and other symptoms alongside your cycle, giving you an integrated view of how serotonin-related changes may be playing out.

Supporting healthy serotonin function

For people whose serotonin-related symptoms are cycle-linked, Nettle™ can help by targeting the brain’s response and top-down regulation hubs directly. Through non-invasive brain stimulation, Nettle engages the prefrontal cortex and connected emotion-regulation networks, supporting steadier mood and emotional control without altering otherwise healthy hormonal patterns.

If your symptoms suggest serotonin imbalance, and especially if they follow a hormonal rhythm, think brain-first. By understanding and supporting the brain’s serotonin system, you can address the root of the problem, not just the symptoms.

References:

Kale, M.B., Wankhede, N.L., Goyanka, B.K. et al. Unveiling the Neurotransmitter Symphony: Dynamic Shifts in Neurotransmitter Levels during Menstruation. Reprod. Sci. 32, 26–40 (2025).

Sacher, J., Zsido, R. G., Barth, C., Zientek, F., Rullmann, M., Luthardt, J., Patt, M., Becker, G. A., Rusjan, P., Witte, A. V., Regenthal, R., Koushik, A., Kratzsch, J., Decker, B., Jogschies, P., Villringer, A., Hesse, S., & Sabri, O. (2023). Increase in serotonin transporter binding in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder across the menstrual cycle: A case-control longitudinal neuroreceptor ligand positron emission tomography imaging study. Biological Psychiatry, 93(12), 1081–1088.

Rubinow, D. R., Schmidt, P. J., & Roca, C. A. (1998). Estrogen–serotonin interactions: Implications for affective regulation. Biological Psychiatry, 44(9), 839–850.

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry 28, 3243–3256 (2023).

Hindberg, I., & Naesh, O. (1992). Serotonin concentrations in plasma and variations during the menstrual cycle. Clinical Chemistry, 38(10), 2087–2089.